Writer's notebook

travel

Give us a kiss!

Has anybody seen those appalling posters on Facebook about the wonders of being British? Something along the lines of how we’d rather walk a mile in tight shoes than complain about our restaurant food, or how we’d probably describe a nuclear strike as a ‘bit warm’? About how marvellously modest and unassuming we are?? I mean, has the person who wrote that ever heard of Jeremy Clarkson? Boris Johnson? Brian Blessed? Or the fans of any football club you care to mention? (I suppose you could make a case for the modesty of Millwall supporters, whose motto is ‘no one likes us, we don’t care’ but only if you’d never heard them in full cry).

Anyway, I have been thinking about Britishness lately because I have just come back from France. And my topic du jour is kissing. We are all kissing each other’s cheeks in Britain now, and I blame the French. Time was, and I’m not that decrepit, when you only kissed your mum and dad. And, possibly, whiskery aunties. And then just a swift peck, mind you, none of this random face pressing that we all seem to be going for these days. No. Back then, we British (if I can get all Facebook postery) made do with a swift handshake and a mumbled hello. In fact, that probably counted as rather imaginative foreplay back in the day.

When I was 17 I was taken by my sister in law (French) to stay in Bordeaux for a week. When we got off the plane an entire phalanx of relatives were lined up (some actually wearing berets) and we all solemnly kissed each other. Took ages. (I have to say at this point, although it is somewhat off piste, that during this visit I was taken to meet some great uncle who was in hospital. He was a lovely, ancient man, aged about 804, tucked tightly into a spotless bed; and he too was wearing a beret. And, naturally enough, we all kissed him. Took ages.

Years later I went to see a friend in France who had teenage children. And get this, when they brought friends home, they all came up to us and kissed us. I was charmed, and somewhat staggered. I could, in no circumstances, think of being approached in Britain by a strange teenager who wanted to kiss me politely on the cheek and wish me good day.

And yet, that day may not be far off. Even now, in the South East, people who’ve known each other for quite a long time are kissing each other when they meet (except my friend Deborah, who refuses to give in to any of this continental canoodling and is hoisting the flag for traditional British circumspection). Brothers and sisters are kissing each other when they greet (yes, really) and er, quite a few other people in situations I can’t think of at the moment. The disease has certainly reached the midlands, but the jury is out on whether it will sweep Yorkshire (it’s the way they stare at you there which kind of brings you to a halt before you properly get to grips with your intended target, and the only way you can alleviate any possible embarrassment is to stop before you get any closer, lift your arms really expansively and say, ‘fancy a pint?’)

Still, think on this. A couple of years ago I was sitting on a train in a French railway station watching out of the window as an inspector tried to pacify a surging crowd of people whose train’s departure had been delayed. Suddenly, down the steps on to the platform came the boss of the whole shebang. Big hat, gold braid, the lot. He marched up to the inspector. The people gesticulated. (As they do.) I thought there was going to be a riot. The inspector turned to his boss. His boss looked at him. And yes. They kissed. Both cheeks. And suddenly, everything was fine. The people got on the train, the inspector got on the train and the boss waved them off as it hooted down the track.

Maybe if it has that kind of effect, we shouldn’t be so uptight. Anyone up for a kiss? Mr Clarkson? Boris?

Picture by Banksy, courtesy of Creative Commons at https://www.flickr.com/photos/leonsteber/1154551362/

China 41: Walking the gangplank

Continuing my 1985 diary of a trip to China March 17

Plane to Nanning. The aircraft is much snazzier than the one to Lhasa and we get free hankies (my second), boxes of chrysanthemum tea (not dried tea; it’s a cold drink) and a compass on a key ring. I don’t know if the compass is supposed to make us feel more confident that the pilot knows what he’s doing, but we get there.

Cheryl and Elspeth were entranced by the news that, according to that guy I met in Cheng Du, you can get pizzas in Nanning. Unfortunately I can’t remember which hotel he said, and we trail round three with no success. Our packs are getting heavier as we are now carrying all our winter clothing. The further south we go, the hotter it gets. We’ll have to get out our shorts, soon. C and E have the heaviest loads with those huge Chinese coats.

Bereft of pizzas, we go back to the hotel where the airport bus dropped us off. There’s some kind of celebration going on; there’s a lion dance in the driveway and sheets of firecrackers. The place is packed and everyone is crowding into a special room (where the tables have tablecloths!). Don’t know if it’s supposed to be a particular function but, amazingly, there’s plenty of space for us. The waitress is friendly and the sweet and sour pork is lovely. A western family is here too. They have a baby and a six-year-old child. Both of them seem really ugly after Chinese children. Maybe they are just really ugly. Bed. My first time under a mosquito net.

March 18

Bus to railway station. Hard seat to Zhan Jiang, which is China’s southernmost town. It’s a nine-hour journey through the sort of countryside that everyone always associates with China – terraced fields; paddy fields, peasants in coolie hats, water buffalo and rich red earth like turmeric powder piled in heaps. It’s getting warmer and warmer.

At Zhan Jiang we get bicycle taxis to the hotel. I’m on the outside and it’s a bit scary when we go round corners. The hotel is a bit of a dump, but clean and cheap. No food. We go round the food stalls buying oranges and bananas for tomorrow’s trip and trying not to look at the varnished brown dog carcases hanging up with the chickens in the pavement cafes. We stop by a woman with buckets of rice and greens on the pavement and have that for tea. It’s cold, but at least it’s not dog.

March 20

Up in the velvety darkness at 5 am for our 6 am bus ride and ferry to Haikou, which is on the island of Hainan Dao. It’s supposed to be marvellously beautiful and unspoilt. It’s also a big military base, and we shouldn’t really be going there, as westerners, but after bottling out of the truck ride to Lhasa we’re going to try it. It’s another trip on the bicycle taxis. This time I sit on the inside, bang next to the back wheel. We get to the bus, and find that the world and his wife and all their pigs and chickens and spring onions are coming too. But, miraculously, we do actually set off at 6. And we’re in front seats, thank god. Some people are standing, and two are sitting on the engine cowling by the driver. Talk about a hot seat.

We go across a river on a raft. We have to get off the bus, which then drives on and we all crowd on after. Everybody spends the short trip fighting like hell to get back on the bus, because as soon as the raft docks the buses drive off – there’s no waiting about. Then we get to the real ferry for Hainan Dao. And, get this, we have to go up a proper gang plank to get on. Well, two planks actually, that wobble, and you have to step over a dead rat. How authentic is that? I feel like I’m in a proper English 20th century novel. Any minute now Peter Ustinov is going to push through the crowds towards us in a linen suit and a Panama hat, or maybe Clark Gable and Jean Harlow are already throwing plates at each other in the restaurant. But sadly not. The boat is just chock full of Chinese people (and pigs and chickens and vegetables) and us. And no restaurant. But, bizarrely, there is a woman selling pink-iced finger buns. We’re very doubtful about them, especially after my experience with the concrete bread rolls in Tibet, but they are lovely. Just like you’d buy in the bakers, back home.

I’m not entirely certain we’re going to get all the way there in one piece. Sealink would probably have sent the ferry for scrap in about 1915. On the up side, there are so many holes in it I get plenty of fresh air and am not seasick, which I was rather worried about.

Amazingly we are here. Another bus from the ferry to Haikou, and yet more bicycle taxis from the bus station to the hotel. It’s properly hot now. There are palm trees which C &E have never seen before in the wild, as it were, and they’re entranced. Elspeth hugs one with delight. ‘They’re great aren’t they?’ she announces. Cheryl is busy examining the patterned bark. I’m sitting on my pack writing this while I wait for them. Anybody would think they’d gone completely bonkers (and I’m sure some passing Chinese people do) but they’ve spent so long in the cold bleakness of northern China that all this lush greenery has completely gone to their heads. They are so happy. Extraordinary.

The hotel is amazing too. All glass and marble and we don’t know if we can afford it. The wall behind the reception desk has clocks showing the time in London and New York. But it’s only five kwai (£1) for a dorm bed. It looks as though they’re still building the place but it will be extremely posh indeed when they’ve finished it. The dormitory has a smoked glass door and white tiles on the floor – it’s like we’ve stumbled into the council chamber in Milton Keynes. However, there is no electricity. There are clerks at the end of the hall who are using candles, and they let us use their private bathroom for a wash.

Elspeth and I go exploring and find a restaurant which has a carpet on the floor and a nice Malaysian bloke who tells us about this coffee shop that sells toast. ‘No bangers and mash for you Brits,’ he laughs, ‘But lot of toast!’ He was dead right. Hot buttered toast. And proper tea. There are a load of young Chinese in, too, and they are all sitting round flashing their digital watches and eating their toast with forks, which they then wave theatrically about while talking very loudly to each other.

Spend the afternoon lying around, having baths and eating McVitites digestive biscuits, which they sell in the hotel shop. The shop sells the oddest things. Roget et Gallet perfumes, Californian wine (30 kwai) a Wrangler denim jacket and personal stereos. I want batteries for mine and point to a stereo in the display case. The bloke in charge gets it out and I point to the battery compartment.

‘Ah, you want batteries,’ he says and shows me two.

‘Yes, that’s exactly what I want,’ I reply.

‘No. Mayo,’ he says and puts them away.

Dinner in the restaurant. The tablecloths are filthy and the waitress sweeps up the leavings with a dirty dustpan and brush. But the service is quick and they are really friendly. The food is delicious; fish with melon, sweet and sour pork, beef with noodles and a huge plate of fried rice. Another big bill (15 kwai) and we begin to realise we haven’t got much money left. Prospects of going to Hong Kong now look definitely dodgy.

In the dorm we are joined by a German couple, two French girls and two Swedish guys. The folding wall down the centre of the room has been pulled out. And there is lots of shouting and shuffling on the other side. So we all creep up, shushing each other and giggling, and peek through the cracks.

All the waitresses from the restaurant are there, and there’s a man fiddling with a tape player. Then, as the strains of Carmen fill the room, he begins to shout instructions and the girls all pair up and start to solemnly tango. And, on our side, we fall silent and feel unaccountably homesick.

China 40: Voices in the night

Continuing my 1985 diary of a trip to China

Woken up by the telephone.

‘Wei!’ yells Cheryl.

‘Wei’ shouts a voice on the other end.

Elspeth and I look blearily at each other. Is this their teacher ringing? Is she going to give the girls permission to go to Hong Kong?

Cheryl is desperately trying to keep up with the flood of Chinese coming out of the telephone. It’s not the teacher.

‘Sorry,’ she says at last. ‘I don’t understand.’

Silence. Then another voice comes on the phone. ‘Hello,’ it says. ‘Can I help you?’

‘Yes,’ says Cheryl. ‘What did the other man want?’

‘No,’ says the voice. ‘What do you want?’

‘I don’t want anything,’ says Cheryl.

‘I don’t think I can help you then,’ says the voice. And rings off.

Kunming is supposed to be the city of eternal spring and this is the first time it has shown any signs of it. The city was really cold when I arrived, although there were lots of flowers (poppies and hollyhocks), but today it’s warm and we go in search of Mr Tong the elusive restaurant owner.

He’s in a completely different part of town to the one we were wandering about in last night. We have to take a couple of buses and walk through some charming streets that look as if they are straight out of Hollywood; very old fashioned houses with curved roofs, lots of plants, little lanes, washing hanging out, and everything looking clean and bright.

One house is actually a hairdressers. It looks like it is someone’s front room, with three women, their hair in curlers sitting on a sofa, reading magazines and waiting their turn.

We walk through Green Lake Park, so called because the scum on the lake is a bright, bright green. There’s lots of building going on. The scaffolding is a crazy network of bamboo, and the bricks look like they’ve been thrown together, but I suppose the builders will cover it all in plaster, and it’ll look really solid.

And we find Mr Tong! He is everything Hannah said he would be, and more. He talks brilliant American. ‘Hey, you guys! How you doing?’ And he keeps patting us fondly on the back. The food is excellent and we get coffee and toffees and memorial chopsticks, just like Hannah’s. Hefty bill though – 17 kwai.

Slow contented walk back to the hotel in the sunshine. We wander through a tourist shop – beautiful china, but very pricey. Elspeth asks the cost of what she thinks is an antique bowl. The shop owner smiles at her. ‘500 kwai, and it’s brand new,’ he says proudly.

China 39: Escape plans

Continuing my 1985 diary of a trip to China We could go to Hong Kong with my credit card! What a lovely idea, all that cheese and hamburgers and cocktails. I think all of us have had enough of being in this country now. I can’t describe what it’s like being here. Like white noise, I suppose. You don’t notice the stress at first. But all the tiny little irritations just pile up and up, until you think your head is going to fall off. We’re all bizarrely unreasonable about ridiculous things, and Cheryl and Elspeth have been here way, way longer than me. I don’t know how they’ve managed it this far without going completely bonkers, like that American girl who smashed plates in Cheng Du. By not thinking too much, probably. Anyway we lie in our beds and discuss how bloody marvellous it would be just to go to Hong Kong, and then we go to the Public Security office, for the girls to get passes, which as students, they need before they can leave the country. And, of course, the office won’t hand over any passes without permission from their teacher in Beijing. Cheryl and Elspeth put through a person to person call in Beijing to try to get their teacher, but without much hope. Its 3.30 and she’s probably already gone home. The rest of the afternoon is spent waiting for the phone to ring, which it does frequently, but it’s only the operator saying, ‘No luck.’ Chinese telephone etiquette is quite startling. When you pick up the phone you yell, ‘Wei!’ and then the person at the other end yells, ‘Wei!’ and then you both pause while you wonder if the other person is still there. Hannah comes around and we go in search of Mr Tong, a ‘lovely little Burmese man’ who, according to her, runs a fantastic restaurant with really good coffee, but he wants to go back to Burma and the Chinese won’t let him. We follow her guide book’s instructions and get totally lost. We stand in the middle of the street and call, ‘Mr Tong!’ plaintively, like lost storks, but no joy, and no smiling Burmese gent, either. A bloke in a Vietnamese coffee bar offers to help, this though he admits he doesn’t like foreigners much, especially Americans, but even after he asks around for us, no one has heard of Mr Tong. In the end we eat at another restaurant where we get excellent food. Hannah rather sadly gets out her memorial chopsticks, given to her by Mr T and then realises he also gave her his card. Duh! We’ll go there tomorrow. Come back via a three storey department store. The counters are exactly as I remember them in Cairds, in Perth when I was about six. Like glass-topped desks. And the goods for sale are all in small enamel pie dishes. None of us can work out what the goods are though. They’re just metal things. But they have some lovely postcards, of beautiful water colour paintings by Pan Tian Shou. I take a packet to the till, and some bloke looks at me in disgust and says, ‘Why are you buying those? What do you know about Pan Tian Shou? You’re just a westerner. You cannot appreciate him.’ But I do. Picture courtesy of Creative Commons via http://arts.cultural-china.com/en/77Arts4565.html

Continuing my 1985 diary of a trip to China We could go to Hong Kong with my credit card! What a lovely idea, all that cheese and hamburgers and cocktails. I think all of us have had enough of being in this country now. I can’t describe what it’s like being here. Like white noise, I suppose. You don’t notice the stress at first. But all the tiny little irritations just pile up and up, until you think your head is going to fall off. We’re all bizarrely unreasonable about ridiculous things, and Cheryl and Elspeth have been here way, way longer than me. I don’t know how they’ve managed it this far without going completely bonkers, like that American girl who smashed plates in Cheng Du. By not thinking too much, probably. Anyway we lie in our beds and discuss how bloody marvellous it would be just to go to Hong Kong, and then we go to the Public Security office, for the girls to get passes, which as students, they need before they can leave the country. And, of course, the office won’t hand over any passes without permission from their teacher in Beijing. Cheryl and Elspeth put through a person to person call in Beijing to try to get their teacher, but without much hope. Its 3.30 and she’s probably already gone home. The rest of the afternoon is spent waiting for the phone to ring, which it does frequently, but it’s only the operator saying, ‘No luck.’ Chinese telephone etiquette is quite startling. When you pick up the phone you yell, ‘Wei!’ and then the person at the other end yells, ‘Wei!’ and then you both pause while you wonder if the other person is still there. Hannah comes around and we go in search of Mr Tong, a ‘lovely little Burmese man’ who, according to her, runs a fantastic restaurant with really good coffee, but he wants to go back to Burma and the Chinese won’t let him. We follow her guide book’s instructions and get totally lost. We stand in the middle of the street and call, ‘Mr Tong!’ plaintively, like lost storks, but no joy, and no smiling Burmese gent, either. A bloke in a Vietnamese coffee bar offers to help, this though he admits he doesn’t like foreigners much, especially Americans, but even after he asks around for us, no one has heard of Mr Tong. In the end we eat at another restaurant where we get excellent food. Hannah rather sadly gets out her memorial chopsticks, given to her by Mr T and then realises he also gave her his card. Duh! We’ll go there tomorrow. Come back via a three storey department store. The counters are exactly as I remember them in Cairds, in Perth when I was about six. Like glass-topped desks. And the goods for sale are all in small enamel pie dishes. None of us can work out what the goods are though. They’re just metal things. But they have some lovely postcards, of beautiful water colour paintings by Pan Tian Shou. I take a packet to the till, and some bloke looks at me in disgust and says, ‘Why are you buying those? What do you know about Pan Tian Shou? You’re just a westerner. You cannot appreciate him.’ But I do. Picture courtesy of Creative Commons via http://arts.cultural-china.com/en/77Arts4565.html

China 38: Money lenders and My Fair Lady

(continuing my 1985 diary of a trip to China and Tibet)

The train pulls in to Kunming just after 7.30 am. Cheryl’s waiting for me at the barrier, and it is so good to see her. We get a bus to the hotel; the old rugger scrum again, but when we get bashed in the mad scramble to get on, I find I can bash back twice as hard with my pack.

She and Elspeth have pushed the boat out and got a three-bed room with a bath (12 kwai each). Breakfast is fried eggs, toast and coffee and I think I’ve died and gone to heaven. Hannah from New York, who I was with in Tibet, is here. She wants to go to Shanghai, but all the planes are booked for a week and she doesn’t want to spend three days on a train. Cheryl goes with her to the CAAC office to see if this is true or if they just can’t be bothered to take her, but they are adamant. No seats.

They are equally tough in my case. We’re flying to Nanning on the way to Hainan Dao (it means literally, South Sea Island) and Cheryl and Elspeth can pay in Renminbi with their student cards, but the office won’t accept my card. The woman behind the counter will not believe I’m a student – no matter how often I tell her my name is Chrysanthemum Wang. Which is sharp of her, but it means I have to pay in FEC, foreign exchange currency. Which is a pain. It means I’m going to have to find a moneylender and go in for a bit of swift mental arithmetic.

I go back to the hotel and change a travellers’ cheque, then I go out in the street and collar a likely looking lad on the corner with a bike. Why do all money-lenders have bikes? (Monumentally stupid question, ed. Just look at all the police strolling about, and ask yourself why you are down a side street with three of the guy’s mates on look-out duty). I change my money with him at a rate of 1.6 into renminbi, and then nip back into the hotel and change it back into FEC with a lad from Sheffield at the rate of 1.4. Total economic madness. But we’ve all made something, and we’re all happy. Except possibly the Central Bank of China, but I don’t know them personally, so it doesn’t bother me. Although how the whole system doesn’t collapse when everybody seems to be winning, I don’t know.

Suppertime is a bit of a disappointment. Practically everthing on the menu is off, so we have a very small meal. We go back to the hotel and eat fried goat’s cheese, which is all they have (and very nice). The bar has a tape player, so I put on Frankie Goes To Hollywood, but the bar staff don’t like this at all and switch it off. But then, when I just laugh and take it away, they tell me to put it back on. They can be such odd people.

Hannah and I go for a walk and discover that we both grew up listening to My Fair Lady. Within seconds we are prancing down the street singing, ‘All I want is a room somewhere’. Hannah’s attempt at a Cockney accent is hysterical and she thinks much the same of my rendition of ‘ahhooOOoodenit be luvverly.’ We are bent over, breathless with laughter, 8,000 miles from home, being carefully skirted by Chinese people who stare at us rather warily. Maybe we have gone loopy. Maybe after all these weeks, the songs of Lerner and Loewe have finally done for us. But who cares, when there’s two of you to sing?

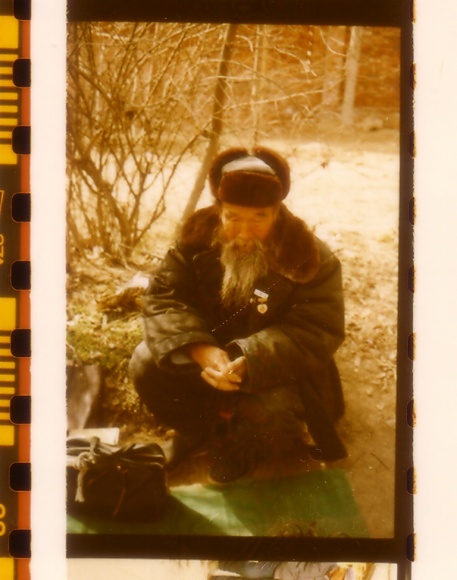

(I apologise for the quality of my pictures at the moment. I’ve had to get a new scanner and the operating system is still waiting to be decoded by Alan Turing).

China 37: Meeting mummy on the train

Get up in the dark for the taxi to the railway station. I’m off to Kunming this morning to meet up with Cheryl and Elspeth. Of course, with China being so big, the trip will take a day or so, but I don’t care. I have a soft sleeper, and it is supposed to be one of the most beautiful railway journeys in the world, hundreds of miles south through the rich tea-growing province of Yunnan.

The taxi is one of those lumbering Morris Oxford jobs. While we are waiting to draw out into the traffic from the hotel, some guy is riding towards us on his bike, but he seems to have fallen asleep; he is nodding over the handlebars, even though his feet are still pedalling. And then he jerks awake, sees us and, trying furiously to brake, falls off. The taxi driver just keeps going and leaves the bloke in the dust.

I get to the station and, because I’ve got a soft-sleeper, the guard leads me to a special spot behind the barrier to wait for the train. It’s not a ‘special’ special spot. It’s just like I’ve been parked. I’m waiting with two spectacular Germans. They’re big, shaggy wild rovers. They have big felt hats, woolly pullies, and packs with all sorts of stuff hanging off; cups and tents and a full canteen of sterling silver cutlery complete with grapefruit knives and a 25-year money-back guarantee. Ok, so I made the last part up. The Chinese are astounded by these men. They are hanging over the barriers gawping; one girl just stares, open-mouthed with her head on one side.

‘Don’t you feel sometimes as if you are in a zoo?’ I ask the men.

‘No,’ says one of the guys. ‘In Germany too, we get stared at.’

The train arrives and I find my compartment. The soft sleeper looks a bit tacky – horrible net curtains, dirty tablecloth, sticky carpet. Still, there’s a plant in a nice pot on the table and the other three occupants are nice too; a soldier, an agricultural professor who keeps dashing out to look at the scenery and a man who works in a chemical plant. There’s also his wife, who sleeps next door, but who spends most of the day in with us. She can’t speak English but she does speak Universal Mother Language and we understand each other perfectly. She’s a little dumpy, cheerful woman and she never stops talking. The soldier lies in one of the top bunks and puts his hat over his face, while she just goes on and on.

‘Look at her,’ she says, pointing at me. ‘All she does is eat chocolate and oranges and drink coffee. It can’t do her any good at all.’ Her husband looks at me, and we both smile. Then she feels the cloth of my ski trousers. ‘Thin, so thin. How does she keep warm? Eh?’ I offer her my jacket and she puts it on. ‘Thin, far too thin. Nice feel, though.’ She gestures at her big blue padded coat, the sort that all the Chinese, and Cheryl and Elspeth wear. ‘That’s what you need to keep the cold out.’ She makes me feel it. ‘Good thick stuff. Warm, hmmm?’

After we eat in the restaurant car, it’s more of the same. ‘Look at her. She uses her chopsticks as though she has one hand tied behind her back. Two hands, dear, like this. Look, look. Like this.’ And, ‘How old are you dear?’ (She does this by by placing her hand parallel to the floor and counting) ‘Don’t you miss your mummy and daddy?’

In the evening another agricultural professor, who can speak English, arrives. He has spent a couple of months in Germany, in Wastephalia as he terms it, and has already met the two German backpackers. The woman leaves for a bit and when I ask the professor to translate exactly what she has been saying, all the other men start laughing. The soldier in the top bunk lifts his hat off his face. ‘Mama, baba,’ he groans theatrically, and everybody laughs again.

The professor is a lovely man. He’s very earnest and, boy, does he love his subject. He tells me that China has almost doubled its agricultural production levels since the revolution and that they are doing the best to reclaim the desert for grazing.

We stand in the corridor and lean against the window while he talks about tea production, and grass growing and behind him the countryside unrolls like a silk painting. Terraced hills in green and yellow, wide rivers, and rice paddies with water buffaloes and people in coolie hats. It is story-book beautiful. (Unfortunately, none of my pictures come out, possibly on account of the camera being dropped down the toilet, so I have posted a picture of a random shack. Hope nobody minds.)

China 36: At home in Cheng Du

Continuing my 1985 diary of a trip to China and Tibet

Back in Cheng Du. I loved Tibet, but it feels so good to be back. Like I’m home or something. In fact, I feel so good that it doesn’t bother me that I have to get a bus to the Jin Jiang hotel, and that I haven’t the faintest idea which bus is the right one. I just climb on the bus that I think is right and all the passengers nod madly when I rather tentatively say, ‘Jin Jiang?’.

It’s funny. In Tibet, the Chinese were easy to dislike; most of the ones I met were arrogant and aggravating. Here, they couldn’t be nicer. All of them are obviously having a conversation about me, and whereas before it would have made me feel so self conscious, now, I don’t care. I do wonder, in passing, what I’m going to do if I’ve got on the wrong bus. But what’s the worst that can happen? Anyway it is the right one. The bus screeches to a halt, right outside the hotel and all the passengers shout, ‘Jin Jiang!’ and about 60 pairs of hands pat me on the shoulder as I make my way out.

The doorman carries my bag to reception. That’s not something I expected to happen either. Must be just a day for general friendliness. Check in and run up the six flights of stairs to my dormitory room. At the top I stop and realise what I’ve just done. I ran up six flights of stairs with my pack, which weighs about 50lbs. And I’m not out of breath. I can’t believe it. But then that’s what being at high altitude does for you. I understand now why all those athletes train in Mexico, or wherever. It’s an amazing feeling. And the air is so good to breathe. Dump my pack on my bed pull out my towel and go for a shower. Honest to God, the dirt that comes off me. My hair is caked in dust. The water going down the plughole is brown. But it is hot water and a proper powerful blast of it too. Lovely, lovely, lovely hot water and soap.

And then, food in the hotel dining hall. Meet Margaret from Leeds. She’s spent the last one and a half years teaching English to giggling Japanese women in Tokyo. It’s apparently feminine to giggle before you’re married in Japan, and then become terribly serene after. Reception has assured Margaret that she’s in a room with two Hong Kong women, but there are three packs in her room, all with men’s underwear peeping out of it. When she asks to be moved they put her in a room with a Japanese professor. I make some fatuous joke about him probably being a martial arts expert. And Margaret, small and demure replies, ‘Oh, that doesn’t matter. So am I.’

Apparently she’s the only Western woman ever to have studied this particular branch of Ju Jitsu, and certainly the only woman black belt in it. It teaches strength through weakness; the less strength you use to overcome your opponent, the better you are. She would have got into her second dan by now, except that her teacher feels she is not quite ready – she can’t completely control her emotions. This is quite important as it’s a lethal sport – there are no competitions because of the danger of killing your opponent.

It turns out that I am the one sharing with the two women from Hong Kong. Very pleasant. Bed is wonderful; soft, big clean – and safe.

China 35: Strangers in the night

Continuing my 1985 diary of a trip to China and Tibet

March 11.

Get down to the depot this morning and get my pack on a lorry going to the airport. Take a last look around the market and buy some prayer scarves and am plagued by three kids who alternately hug me and kick me in the shins. Say my goodbyes to Agnetha and Michael and Mick and Julie, and get the bus to the airport. Remember to sit fairly close up front this time, so that I don’t go flying when it hits a pot hole. Still, the journey is not too bad. It takes four hours and there are times when I think we’re having an accident, but no, we are not careering out of control down a ravine, we are merely being driven rather excitingly down a hill that hasn’t got a road yet.

The airport hostel is appalling. The latrines are overflowing and I find I’m sharing a dormitory with a bloke from Saudi Arabia. He seems okay, but he has a master’s degree in moaning. He’s is the most miserable person I’ve ever met. More miserable than a friend’s great aunt, who used to tell people, ‘Ooh, you go on. I’ve had my life.’

He’s been here since his plane arrived this morning and he dislikes the look of the place so much, that he can’t be arsed to go to Lhasa. He just wants to fly straight to Shanghai. ‘I thought it would be a magical place,’ he intones. ‘All green and misty but it is just desert. If I wanted sand I would stay at home.’ At which I giggle. But he just goes on and on.

I leave the room and try to see if I can get into another dormitory, but they are all full up. All the other people here are Chinese and seem mystified that I don’t want to share a room with a strange man. After all, he’s another westerner, isn’t he? None of them are really bothered about my problems, but one bloke, at least, gives me some ink for my pen.

Back to the room. Misery Guts is lying on his bed swigging from a bottle of rice wine and staring at the ceiling. ‘I thought this place would be Shangri La,’ he intones. ‘It is not what I thought.’ I try telling him that I felt much the same way when I arrived, and that he should at least take a look at Lhasa. But he won’t listen. Moan, moan, moan.

He’s also fed up because the airport won’t take travellers’ cheques and he hasn’t got enough money to pay for his ticket. He wants to borrow money from me. He is astounded when I tell him I don’t have enough. Even if I did I wouldn’t lend it to him – but I don’t tell him that. He is going to have to go to Lhasa to change his cheques. The thought makes him even more miserable.

He starts on about his headache. I tell him this is probably because of the altitude. But he’s having none of it.

‘Altitude? Altitude? I am used to altitude. It is this terrible cold I have. Oh this place. Oh how terrible I feel. Why did I come here?’

At least he’s at the other end of the room (although it’s not a very big room). At 10pm the lights are switched off by central control. This is creepy, and it makes him grumble even more but, eventually, he falls silent. I shut my eyes, but I don’t sleep.

At 5.30 he looms over me in the darkness.

‘Did you sleep well?’ he asks.

‘Yes,’ I say warily. He is far too close, and I don’t like the silky tone of his voice.

‘Can I get into bed with you for a warm?’ He is pulling at my sleeping bag.

‘No, you bloody can’t.’

‘Why not?’ he asks. He is, can you believe it, offended.

‘What do you mean, why not?’ I say.

‘But I thought all you western girls have sex with everybody you meet.’

‘Go. Away.’ If he tries anything more, I’m going to sock him.

But, amazingly, he goes. I get up, which is easy because I slept in my clothes, get my stuff packed and get out. But there is nowhere to go. The waiting room is locked and eventually I make my way to the canteen. The Chinese man, who gave me the ink last night, arrives and starts chatting. He talks apologetically about the state of the airport and I think he is quite taken aback, when I just let rip about the sleeping arrangements. Poor bloke. It’s not his fault.

And then I discover I don’t have enough change to pay for my breakfast, so he insists on paying the difference. It is rice porridge, diced raw turnips and four dry biscuits. I know it’s silly, but I cry.

China 34, A lesson in gold smuggling

March 10.

Don’t think I’ll be going anywhere today. We were planning to borrow bicycles and go the Drepong monastery, but after last night, I can’t even summon up enough energy to go with the others to the Dalai Lama’s summer palace, which is much nearer and has a western bog and a Philips radiogram, according to Michael, the gold smuggler.

Michael is a terribly serious, young(ish) bloke who comes from Cricklewood, and who is attempting to learn how to do the Daily Telegraph cryptic crossword. He used to work in a dole office, apparently, advising claimants on how to fill in their UB40s, and now he runs a smuggling ring from Korea to India. Amazing the turns a career can take.

I don’t know why he wants to learn how to do cryptic crosswords. It’s not as if he needs something to do on the 8.10 to Liverpool Street every morning. And commuters only do the crossword so that they don’t have to speak to any of their fellow human beings. I keep thinking of that scene in James Bond where 007 says, ‘Do you expect me to talk?’

In my mind, Goldfinger is replying, ‘No Mr Bond, I expect you to help me with 24 Across.’

Still, Michael is earnestly insistent that I unlock the mysteries for him, and in between wondering if I’m going to heave again, I do my best. He has a much-thumbed paperback of crosswords, and we go through them slowly.

‘It’s like a secret code,’ he says. ‘And nobody ever tells you how to crack it.’

Julie works for him, as a mule. She’s an ex teacher but she got bored with her husband who was an accountant and who wore shirts with contrasting collars. She had a hatchback and an executive house with fully fitted carpets and she and her husband went to fondue parties and drank Mateus rose, and one day she bought a backpack and went to India. When her savings ran out she did a few little trips for Michael and apparently it’s very lucrative. He pays $600 per trip.

I thought about doing it too, for about 30 seconds. The money is very good. But I’m not too keen on inserting two lumps of gold the size of large torch batteries, into my bum. You get on the plane to India and when you get off you are met by a taxi driver who takes you to a pre-arranged meet, where you produce the gold and get the dosh. But it doesn’t always work out like that.

‘Sometimes the taxi drivers have been bribed by a rival gang to take you to the police station instead,’ Julie told me. ‘That’s what happened to me. And I just kept telling the police I had no idea what was happening, and that I was just an innocent tourist, and they said they would let nature take its course. So I just hung about in the station doing my yoga exercises to show that I hadn’t a care in the world, even though, ohhh, that gold was really hurting. But then some more money must have changed hands because they let me go. And everything was fine.’

Everything, except, possibly, her backside, where she could now keep her rucksack.

China 33, The invisible monk

Continuing my 1985 diary of a trip to China and Tibet

The Potala Palace is a hell of a climb, just to get to the main doors, and made even more difficult by the fact that the Tibetans like their steps to be steep. But when we eventually get to the first entrance, the main door is closed. Agnetha is gasping for a pee, and there’s no one about so she just squats by a wall. I can’t resist it; I get my camera out. Horrified, she stands up and her trousers fall down. Naturally, I think this is hysterically funny and we run up to the next level, shouting and laughing. I don’t know what’s got into us. Neither of us would behave like this outside Buckingham Palace, or the Royal Palace in Stockholm. But there is no one to hear or see us. We’re like seven-year-olds, skidding at last into a large, open, almost deserted courtyard.

At one end is an entrance to a temple and we buy the inevitable ticket and remember where we are. Up we climb again. This whole place, the official residence of the Dalai Lama, is a maze of tunnels and walkways. There is an open square, several storeys high, with balconies. There is a little bridge from the balcony we are on, to a central building. We go across to it and it is a restaurant. Closed. Looks sort of Chinese 1930s style again. Can’t imagine the monks using it. Peeking through a chink in the curtains I can see a Bakelite telephone. Direct line to the Dalai Lama? I doubt it somehow.

There are doors everywhere. Some lead to tiny little rooms, some to huge ones. A monk, with pads under his feet (to keep the floors polished?) smiles and points at Agnetha’s camera, but no, we haven’t got pictures of the Dalai Lama. He is a wonderful old monk and is all smiles when we want to take his picture.

We find another room, one with white pendant lamps like you get in a wine bar at home. There are Buddhas everywhere. And in front of all of them are bowls of yak butter and money and white prayer scarves and green grass growing in empty mandarin orange tins. The buddhas are magnificent. God knows what they are made of – solid gold probably. And there are great knobbly chunks of turquoise just lying about. Hanging from the ceiling in one room are child-size red hand prints on white silk – with evenly spaced dark dots on them. Are these the marks of the Dalai Lama as a child? Dunno. There is hardly anybody about – we seem completely free to explore. I so desperately want to find a secret passage, but I stop myself from prodding likely looking knobs.

As we wander deeper and deeper in to the palace the silent reverence of the place makes us fall silent and, when we do talk, it’s in slow whispers. We have become so awestruck by all this dim mysterious magnificence that when we are approached by a monk with a tin of toffees, we don’t know what to do. I’m particularly struck by the fact that they are Bluebird Toffees, just like my great auntie Maggie used to have, and that there is a picture of what looks like Edinburgh Castle on the lid. He says something and shakes the tin at us so, very respectfully, we take a sweet each and then look at each other.

‘Are we supposed to give them to Buddha as offerings?’ says Agnetha.

I don’t know. We hold the toffees reverently and look at the monk for guidance. He seems rather exasperated. Finally he points at the sweets and then points at his mouth, as if he were dealing with a very slow pair of children. I begin to giggle, and then, much to his obvious relief, we undo the waxed paper wrappings (each with a little picture of a bluebird on it) and start chewing the toffees. They taste so good. We’re still chewing when we walk into another room which has a beautiful, stylised painting of Lhasa on the wall. The monk who has led the way, points out the Potala and the Sera and the Jhokang, and then points to another and shakes his head sadly – this monastery was razed to the ground by the Chinese during the cultural revolution.

At the doorway to the Dalai Lama’s bedroom, two monks sell us tickets to have a look. You can’t actually go in, though. An American who has arrived doesn’t have any change, but it doesn’t matter - one of the monks gets the change from offerings thrown into a roped-off part of the sitting room.

And boy, does that guy have sitting rooms. There are five, that we see, and in each his chair has his empty coat and hat on it. Some of the monks must sleep in these rooms because, in each, there are little towels, neatly folded, with bowls of yak butter tea here and there.

As we come out, back into the great courtyard, we meet the old monk again, now accompanied by a boy monk who says the old man wants to know our names. So we tell him and he tells us that he is Lama Namideya, or something that sounds like that, anyway. He poses cheerfully again for a picture.

On the way back to the hotel, as I am crowing about finally getting decent photograph, Agnetha shakes her head.

‘Tibetan monks can disappear from pictures, you know,’ she says.

‘Don’t be daft.’

‘It is true. They pose for pictures and then when you get them developed, not nobody is there.’

‘Sounds like the kind of pictures my mother takes,’ I say cheerfully, and we meet up with the others and go off to a restaurant where we’re all given a basin of lamb bones to gnaw on. It’s so mediaeval I have to stop myself from throwing my used bones on the floor. They taste great, but in the middle of the night I get up and am totally and fabulously sick.

Months later, when I get my pictures developed, I don’t have a single one of the monk and his boy.